Chapter 1 Why Statistics?

To call in statisticians after the experiment is done may be no more than asking them to perform a post-mortem examination: They may be able to say what the experiment died of. —Sir Ronald Fisher

1.1 On the psychology of statistics

Adapted nearly verbatim from Chapters 1 and 2 in Navarro, D. “Learning Statistics with R.” https://compcogscisydney.org/learning-statistics-with-r/

To the surprise of many students, statistics is a fairly significant part of a psychological education. To the surprise of no-one, statistics is very rarely the favorite part of one’s psychological education. After all, if you really loved the idea of doing statistics, you’d probably be enrolled in a statistics class right now, not a psychology class. So, not surprisingly, there’s a pretty large proportion of the student base that isn’t happy about the fact that psychology has so much statistics in it. In view of this, I thought that the right place to start might be to answer some of the more common questions that people have about stats…

A big part of this issue at hand relates to the very idea of statistics. What is it? What’s it there for? And why are scientists so bloody obsessed with it? These are all good questions, when you think about it. So let’s start with the last one. As a group, scientists seem to be bizarrely fixated on running statistical tests on everything. In fact, we use statistics so often that we sometimes forget to explain to people why we do. It’s a kind of article of faith among scientists – and especially social scientists – that your findings can’t be trusted until you’ve done some stats. Undergraduate students might be forgiven for thinking that we’re all completely mad, because no-one takes the time to answer one very simple question:

Why do you do statistics? Why don’t scientists just use common sense?

It’s a naive question in some ways, but most good questions are. There’s a lot of good answers to it, but for my money, the best answer is a really simple one: we don’t trust ourselves enough. We worry that we’re human, and susceptible to all of the biases, temptations and frailties that humans suffer from. Much of statistics is basically a safeguard. Using “common sense” to evaluate evidence means trusting gut instincts, relying on verbal arguments and on using the raw power of human reason to come up with the right answer. Most scientists don’t think this approach is likely to work.

In fact, come to think of it, this sounds a lot like a psychological question to me, and since I do work in a psychology department, it seems like a good idea to dig a little deeper here. Is it really plausible to think that this “common sense” approach is very trustworthy? Verbal arguments have to be constructed in language, and all languages have biases – some things are harder to say than others, and not necessarily because they’re false (e.g., quantum electrodynamics is a good theory, but hard to explain in words). The instincts of our “gut” aren’t designed to solve scientific problems, they’re designed to handle day to day inferences – and given that biological evolution is slower than cultural change, we should say that they’re designed to solve the day to day problems for a different world than the one we live in. Most fundamentally, reasoning sensibly requires people to engage in “induction,” making wise guesses and going beyond the immediate evidence of the senses to make generalisations about the world. If you think that you can do that without being influenced by various distractors, well, I have a bridge in Brooklyn I’d like to sell you. Heck, as the next section shows, we can’t even solve “deductive” problems (ones where no guessing is required) without being influenced by our pre-existing biases.

1.1.1 The curse of belief bias

People are mostly pretty smart. We’re certainly smarter than the other species that we share the planet with (though many people might disagree). Our minds are quite amazing things, and we seem to be capable of the most incredible feats of thought and reason. That doesn’t make us perfect though. And among the many things that psychologists have shown over the years is that we really do find it hard to be neutral, to evaluate evidence impartially and without being swayed by pre-existing biases. A good example of this is the belief bias effect in logical reasoning: if you ask people to decide whether a particular argument is logically valid (i.e., conclusion would be true if the premises were true), we tend to be influenced by the believability of the conclusion, even when we shouldn’t. For instance, here’s a valid argument where the conclusion is believable:

- No cigarettes are inexpensive (Premise 1)

- Some addictive things are inexpensive (Premise 2)

- Therefore, some addictive things are not cigarettes (Conclusion)

And here’s a valid argument where the conclusion is not believable:

- No addictive things are inexpensive (Premise 1)

- Some cigarettes are inexpensive (Premise 2)

- Therefore, some cigarettes are not addictive (Conclusion)

The logical structure of argument #2 is identical to the structure of argument #1, and they’re both valid. However, in the second argument, there are good reasons to think that premise 1 is incorrect, and as a result it’s probably the case that the conclusion is also incorrect. But that’s entirely irrelevant to the topic at hand: an argument is deductively valid if the conclusion is a logical consequence of the premises. That is, a valid argument doesn’t have to involve true statements.

On the other hand, here’s an invalid argument that has a believable conclusion:

- No addictive things are inexpensive (Premise 1)

- Some cigarettes are inexpensive (Premise 2)

- Therefore, some addictive things are not cigarettes (Conclusion)

And finally, an invalid argument with an unbelievable conclusion:

- No cigarettes are inexpensive (Premise 1)

- Some addictive things are inexpensive (Premise 2)

- Therefore, some cigarettes are not addictive (Conclusion)

Now, suppose that people really are perfectly able to set aside their pre-existing biases about what is true and what isn’t, and purely evaluate an argument on its logical merits. We’d expect 100% of people to say that the valid arguments are valid, and 0% of people to say that the invalid arguments are valid. So if you ran an experiment looking at this, you’d expect to see data like this:

| conlusion feels true | conclusion feels false | |

|---|---|---|

| argument is valid | 100% say “valid” | 100% say “valid” |

| argument is invalid | 0% say “valid” | 0% say “valid” |

If the psychological data looked like this (or even a good approximation to this), we might feel safe in just trusting our gut instincts. That is, it’d be perfectly okay just to let scientists evaluate data based on their common sense, and not bother with all this murky statistics stuff. However, you guys have taken psych classes, and by now you probably know where this is going.

In a classic study, Evans, Barston, and Pollard (1983) ran an experiment looking at exactly this. What they found is that when pre-existing biases (i.e., beliefs) were in agreement with the structure of the data, everything went the way you’d hope:

| conlusion feels true | conclusion feels false | |

|---|---|---|

| argument is valid | 92% say “valid” | – |

| argument is invalid | – | 8% say “valid” |

Not perfect, but that’s pretty good. But look what happens when our intuitive feelings about the truth of the conclusion run against the logical structure of the argument:

| conlusion feels true | conclusion feels false | |

|---|---|---|

| argument is valid | 92% say “valid” | 46% say “valid” |

| argument is invalid | 92% say “valid” | 8% say “valid” |

Oh dear, that’s not as good. Apparently, when people are presented with a strong argument that contradicts our pre-existing beliefs, we find it pretty hard to even perceive it to be a strong argument (people only did so 46% of the time). Even worse, when people are presented with a weak argument that agrees with our pre-existing biases, almost no-one can see that the argument is weak (people got that one wrong 92% of the time!)

If you think about it, it’s not as if these data are horribly damning. Overall, people did do better than chance at compensating for their prior biases, since about 60% of people’s judgements were correct (you’d expect 50% by chance). Even so, if you were a professional “evaluator of evidence,” and someone came along and offered you a magic tool that improves your chances of making the right decision from 60% to (say) 95%, you’d probably jump at it, right? Of course you would. Thankfully, we actually do have a tool that can do this. But it’s not magic, it’s statistics. So that’s reason #1 why scientists love statistics. It’s just too easy for us to “believe what we want to believe”; so if we want to “believe in the data” instead, we’re going to need a bit of help to keep our personal biases under control. That’s what statistics does: it helps keep us honest.

1.2 The cautionary tale of Simpson’s paradox

The following is a true story (I think…). In 1973, the University of California, Berkeley had some worries about the admissions of students into their postgraduate courses. Specifically, the thing that caused the problem was that the gender breakdown of their admissions, which looked like this:

| Number of applicants | Percent admitted | |

| Males | 8442 | 44% |

| Females | 4321 | 35% |

and they were worried about being sued. Given that there were nearly 13,000 applicants, a difference of 9% in admission rates between males and females is just way too big to be a coincidence. Pretty compelling data, right? And if I were to say to you that these data actually reflect a weak bias in favour of women (sort of!), you’d probably think that I was either crazy or sexist.

Earlier versions of these notes incorrectly suggested that they actually were sued – apparently that’s not true. There’s a nice commentary on this here: https://www.refsmmat.com/posts/2016-05-08-simpsons-paradox-berkeley.html. A big thank you to Wilfried Van Hirtum for pointing this out to me!

When people started looking more carefully at the admissions data (Bickel, Hammel, and O’Connell 1975) they told a rather different story. Specifically, when they looked at it on a department by department basis, it turned out that most of the departments actually had a slightly higher success rate for female applicants than for male applicants. The table below shows the admission figures for the six largest departments (with the names of the departments removed for privacy reasons):

| Department | Applicants | Percent admitted | Applicants | Percent admitted |

| A | 825 | 62% | 108 | 82% |

| B | 560 | 63% | 25 | 68% |

| C | 325 | 37% | 593 | 34% |

| D | 417 | 33% | 375 | 35% |

| E | 191 | 28% | 393 | 24% |

| F | 272 | 6% | 341 | 7% |

Remarkably, most departments had a higher rate of admissions for females than for males! Yet the overall rate of admission across the university for females was lower than for males. How can this be? How can both of these statements be true at the same time?

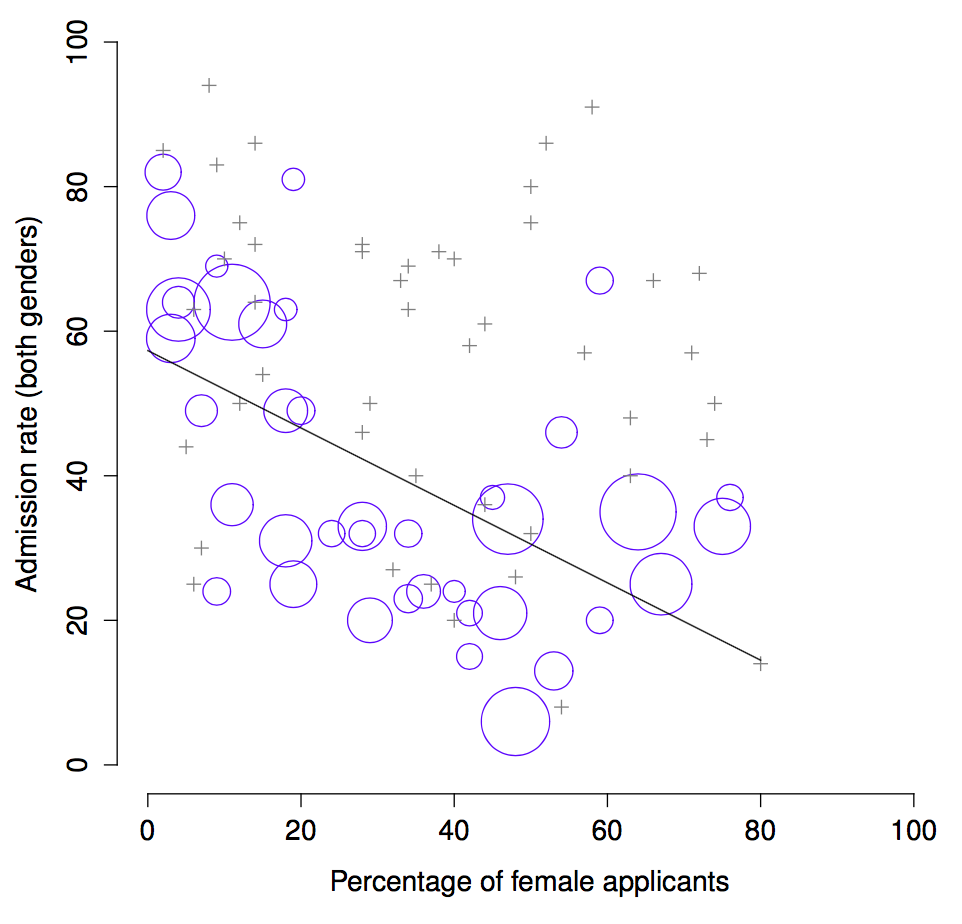

Here’s what’s going on. Firstly, notice that the departments are not equal to one another in terms of their admission percentages: some departments (e.g., engineering, chemistry) tended to admit a high percentage of the qualified applicants, whereas others (e.g., English) tended to reject most of the candidates, even if they were high quality. So, among the six departments shown above, notice that department A is the most generous, followed by B, C, D, E and F in that order. Next, notice that males and females tended to apply to different departments. If we rank the departments in terms of the total number of male applicants, we get A\(>\)B\(>\)D\(>\)C\(>\)F\(>\)E (the “easy” departments are in bold). On the whole, males tended to apply to the departments that had high admission rates. Now compare this to how the female applicants distributed themselves. Ranking the departments in terms of the total number of female applicants produces a quite different ordering C\(>\)E\(>\)D\(>\)F\(>\)A\(>\)B. In other words, what these data seem to be suggesting is that the female applicants tended to apply to “harder” departments. And in fact, if we look at all Figure 1.1 we see that this trend is systematic, and quite striking. This effect is known as Simpson’s paradox. It’s not common, but it does happen in real life, and most people are very surprised by it when they first encounter it, and many people refuse to even believe that it’s real. It is very real. And while there are lots of very subtle statistical lessons buried in there, I want to use it to make a much more important point …doing research is hard, and there are lots of subtle, counterintuitive traps lying in wait for the unwary. That’s reason #2 why scientists love statistics, and why we teach research methods. Because science is hard, and the truth is sometimes cunningly hidden in the nooks and crannies of complicated data.

knitr::include_graphics("figures/1Simpson.png")

Figure 1.1: The Berkeley 1973 college admissions data. This figure plots the admission rate for the 85 departments that had at least one female applicant, as a function of the percentage of applicants that were female. The plot is a redrawing of Figure 1 from Bickel et al. (1975). Circles plot departments with more than 40 applicants; the area of the circle is proportional to the total number of applicants. The crosses plot department with fewer than 40 applicants.

Before leaving this topic entirely, I want to point out something else really critical that is often overlooked in a research methods class. Statistics only solves part of the problem. Remember that we started all this with the concern that Berkeley’s admissions processes might be unfairly biased against female applicants. When we looked at the “aggregated” data, it did seem like the university was discriminating against women, but when we “disaggregate” and looked at the individual behaviour of all the departments, it turned out that the actual departments were, if anything, slightly biased in favour of women. The gender bias in total admissions was caused by the fact that women tended to self-select for harder departments. From a legal perspective, that would probably put the university in the clear. Postgraduate admissions are determined at the level of the individual department (and there are good reasons to do that), and at the level of individual departments, the decisions are more or less unbiased (the weak bias in favour of females at that level is small, and not consistent across departments). Since the university can’t dictate which departments people choose to apply to, and the decision making takes place at the level of the department it can hardly be held accountable for any biases that those choices produce.

That was the basis for my somewhat glib remarks earlier, but that’s not exactly the whole story, is it? After all, if we’re interested in this from a more sociological and psychological perspective, we might want to ask why there are such strong gender differences in applications. Why do males tend to apply to engineering more often than females, and why is this reversed for the English department? And why is it it the case that the departments that tend to have a female-application bias tend to have lower overall admission rates than those departments that have a male-application bias? Might this not still reflect a gender bias, even though every single department is itself unbiased? It might. Suppose, hypothetically, that males preferred to apply to “hard sciences” and females prefer “humanities.” And suppose further that the reason for why the humanities departments have low admission rates is because the government doesn’t want to fund the humanities (spots in Ph.D. programs, for instance, are often tied to government funded research projects). Does that constitute a gender bias? Or just an unenlightened view of the value of the humanities? What if someone at a high level in the government cut the humanities funds because they felt that the humanities are “useless chick stuff.” That seems pretty blatantly gender biased. None of this falls within the purview of statistics, but it matters to the research project. If you’re interested in the overall structural effects of subtle gender biases, then you probably want to look at both the aggregated and disaggregated data. If you’re interested in the decision making process at Berkeley itself then you’re probably only interested in the disaggregated data.

In short there are a lot of critical questions that you can’t answer with statistics, but the answers to those questions will have a huge impact on how you analyse and interpret data. And this is the reason why you should always think of statistics as a tool to help you learn about your data, no more and no less. It’s a powerful tool to that end, but there’s no substitute for careful thought.

1.3 Statistics in psychology

I hope that the discussion above helped explain why science in general is so focused on statistics. But I’m guessing that you have a lot more questions about what role statistics plays in psychology, and specifically why psychology classes always devote so many lectures to stats. So here’s my attempt to answer a few of them…

- Why does psychology have so much statistics?

To be perfectly honest, there’s a few different reasons, some of which are better than others. The most important reason is that psychology is a statistical science. What I mean by that is that the “things” that we study are people. Real, complicated, gloriously messy, infuriatingly perverse people. The “things” of physics include objects like electrons, and while there are all sorts of complexities that arise in physics, electrons don’t have minds of their own. They don’t have opinions, they don’t differ from each other in weird and arbitrary ways, they don’t get bored in the middle of an experiment, and they don’t get angry at the experimenter and then deliberately try to sabotage the data set. At a fundamental level psychology is harder than physics.

Basically, we teach statistics to you as psychologists because you need to be better at stats than physicists. There’s actually a saying used sometimes in physics, to the effect that “if your experiment needs statistics, you should have done a better experiment.” They have the luxury of being able to say that because their objects of study are pathetically simple in comparison to the vast mess that confronts social scientists. It’s not just psychology, really: most social sciences are desperately reliant on statistics. Not because we’re bad experimenters, but because we’ve picked a harder problem to solve. We teach you stats because you really, really need it.

- Can’t someone else do the statistics?

To some extent, but not completely. It’s true that you don’t need to become a fully trained statistician just to do psychology, but you do need to reach a certain level of statistical competence. In my view, there’s three reasons that every psychological researcher ought to be able to do basic statistics:

There’s the fundamental reason: statistics is deeply intertwined with research design. If you want to be good at designing psychological studies, you need to at least understand the basics of stats.

If you want to be good at the psychological side of the research, then you need to be able to understand the psychological literature, right? But almost every paper in the psychological literature reports the results of statistical analyses. So if you really want to understand the psychology, you need to be able to understand what other people did with their data. And that means understanding a certain amount of statistics.

There’s a big practical problem with being dependent on other people to do all your statistics: statistical analysis is expensive. In almost any real life situation where you want to do psychological research, the cruel facts will be that you don’t have enough money to afford a statistician. So the economics of the situation mean that you have to be pretty self-sufficient.

Note that a lot of these reasons generalize beyond researchers. If you want to be a practicing psychologist and stay on top of the field, it helps to be able to read the scientific literature, which relies pretty heavily on statistics.

- I don’t care about jobs, research, or clinical work. Do I need statistics?

Okay, now you’re just messing with me. Still, I think it should matter to you too. Statistics should matter to you in the same way that statistics should matter to everyone: we live in the 21st century, and data are everywhere. Frankly, given the world in which we live these days, a basic knowledge of statistics is pretty damn close to a survival tool! Which is the topic of the next section…

1.4 Statistics in everyday life

“We are drowning in information,

but we are starved for knowledge”

– Various authors, original probably John Naisbitt

When I started writing up my lecture notes I took the 20 most recent news articles posted to the ABC news website. Of those 20 articles, it turned out that 8 of them involved a discussion of something that I would call a statistical topic; 6 of those made a mistake. The most common error, if you’re curious, was failing to report baseline data (e.g., the article mentions that 5% of people in situation X have some characteristic Y, but doesn’t say how common the characteristic is for everyone else!) The point I’m trying to make here isn’t that journalists are bad at statistics (though they almost always are), it’s that a basic knowledge of statistics is very helpful for trying to figure out when someone else is either making a mistake or even lying to you. Perhaps, one of the biggest things that a knowledge of statistics does to you is cause you to get angry at the newspaper or the internet on a far more frequent basis :).

1.5 There’s more to research methods than statistics

So far, most of what I’ve talked about is statistics, and so you’d be forgiven for thinking that statistics is all I care about in life. To be fair, you wouldn’t be far wrong, but research methodology is a broader concept than statistics. So most research methods courses will cover a lot of topics that relate much more to the pragmatics of research design, and in particular the issues that you encounter when trying to do research with humans. However, about 99% of student fears relate to the statistics part of the course, so I’ve focused on the stats in this discussion, and hopefully I’ve convinced you that statistics matters, and more importantly, that it’s not to be feared. That being said, it’s pretty typical for introductory research methods classes to be very stats-heavy. This is not (usually) because the lecturers are evil people. Quite the contrary, in fact. Introductory classes focus a lot on the statistics because you almost always find yourself needing statistics before you need the other research methods training. Why? Because almost all of your assignments in other classes will rely on statistical training, to a much greater extent than they rely on other methodological tools. It’s not common for undergraduate assignments to require you to design your own study from the ground up (in which case you would need to know a lot about research design), but it is common for assignments to ask you to analyse and interpret data that were collected in a study that someone else designed (in which case you need statistics). In that sense, from the perspective of allowing you to do well in all your other classes, the statistics is more urgent.

But note that “urgent” is different from “important” – they both matter. I really do want to stress that research design is just as important as data analysis, and this book does spend a fair amount of time on it. However, while statistics has a kind of universality, and provides a set of core tools that are useful for most types of psychological research, the research methods side isn’t quite so universal. There are some general principles that everyone should think about, but a lot of research design is very idiosyncratic, and is specific to the area of research that you want to engage in. To the extent that it’s the details that matter, those details don’t usually show up in an introductory stats and research methods class.

1.6 A brief introduction to research design

In this chapter, we’re going to start thinking about the basic ideas that go into designing a study, collecting data, checking whether your data collection works, and so on. It won’t give you enough information to allow you to design studies of your own, but it will give you a lot of the basic tools that you need to assess the studies done by other people. However, since the focus of this book is much more on data analysis than on data collection, I’m only giving a very brief overview. Note that this chapter is “special” in two ways. Firstly, it’s much more psychology-specific than the later chapters. Secondly, it focuses much more heavily on the scientific problem of research methodology, and much less on the statistical problem of data analysis. Nevertheless, the two problems are related to one another, so it’s traditional for stats textbooks to discuss the problem in a little detail. This chapter relies heavily on Campbell and Stanley (1963) for the discussion of study design, and Stevens (1946) for the discussion of scales of measurement. Later versions will attempt to be more precise in the citations.

1.7 Introduction to psychological measurement

The first thing to understand is data collection can be thought of as a kind of measurement. That is, what we’re trying to do here is measure something about human behaviour or the human mind. What do I mean by “measurement?”

1.7.1 Some thoughts about psychological measurement

Measurement itself is a subtle concept, but basically it comes down to finding some way of assigning numbers, or labels, or some other kind of well-defined descriptions to “stuff.” So, any of the following would count as a psychological measurement:

My age is 33 years.

I do not like anchovies.

My chromosomal gender is male.

My self-identified gender is male.

In the short list above, the bolded part is “the thing to be measured,” and the italicized part is “the measurement itself.” In fact, we can expand on this a little bit, by thinking about the set of possible measurements that could have arisen in each case:

My age (in years) could have been 0, 1, 2, 3 …, etc. The upper bound on what my age could possibly be is a bit fuzzy, but in practice you’d be safe in saying that the largest possible age is 150, since no human has ever lived that long.

When asked if I like anchovies, I might have said that I do, or I do not, or I have no opinion, or I sometimes do.

My chromosomal gender is almost certainly going to be male (XY) or female (XX), but there are a few other possibilities. I could also have Klinfelter’s syndrome (XXY), which is more similar to male than to female. And I imagine there are other possibilities too.

My self-identified gender is also very likely to be male or female, but it doesn’t have to agree with my chromosomal gender. I may also choose to identify with neither, or to explicitly call myself transgender.

As you can see, for some things (like age) it seems fairly obvious what the set of possible measurements should be, whereas for other things it gets a bit tricky. But I want to point out that even in the case of someone’s age, it’s much more subtle than this. For instance, in the example above, I assumed that it was okay to measure age in years. But if you’re a developmental psychologist, that’s way too crude, and so you often measure age in years and months (if a child is 2 years and 11 months, this is usually written as “2;11”). If you’re interested in newborns, you might want to measure age in days since birth, maybe even hours since birth. In other words, the way in which you specify the allowable measurement values is important.

Looking at this a bit more closely, you might also realise that the concept of “age” isn’t actually all that precise. In general, when we say “age” we implicitly mean “the length of time since birth.” But that’s not always the right way to do it. Suppose you’re interested in how newborn babies control their eye movements. If you’re interested in kids that young, you might also start to worry that “birth” is not the only meaningful point in time to care about. If Baby Alice is born 3 weeks premature and Baby Bianca is born 1 week late, would it really make sense to say that they are the “same age” if we encountered them “2 hours after birth?” In one sense, yes: by social convention, we use birth as our reference point for talking about age in everyday life, since it defines the amount of time the person has been operating as an independent entity in the world, but from a scientific perspective that’s not the only thing we care about. When we think about the biology of human beings, it’s often useful to think of ourselves as organisms that have been growing and maturing since conception, and from that perspective Alice and Bianca aren’t the same age at all. So you might want to define the concept of “age” in two different ways: the length of time since conception, and the length of time since birth. When dealing with adults, it won’t make much difference, but when dealing with newborns it might.

Moving beyond these issues, there’s the question of methodology. What specific “measurement method” are you going to use to find out someone’s age? As before, there are lots of different possibilities:

You could just ask people “how old are you?” The method of self-report is fast, cheap and easy, but it only works with people old enough to understand the question, and some people lie about their age.

You could ask an authority (e.g., a parent) “how old is your child?” This method is fast, and when dealing with kids it’s not all that hard since the parent is almost always around. It doesn’t work as well if you want to know “age since conception,” since a lot of parents can’t say for sure when conception took place. For that, you might need a different authority (e.g., an obstetrician).

You could look up official records, like birth certificates. This is time consuming and annoying, but it has its uses (e.g., if the person is now dead).

1.7.2 Operationalization: defining your measurement

All of the ideas discussed in the previous section all relate to the concept of operationalization. To be a bit more precise about the idea, operationalization is the process by which we take a meaningful but somewhat vague concept, and turn it into a precise measurement. The process of operationalization can involve several different things:

Being precise about what you are trying to measure: For instance, does “age” mean “time since birth” or “time since conception” in the context of your research?

Determining what method you will use to measure it: Will you use self-report to measure age, ask a parent, or look up an official record? If you’re using self-report, how will you phrase the question?

Defining the set of the allowable values that the measurement can take: Note that these values don’t always have to be numerical, though they often are. When measuring age, the values are numerical, but we still need to think carefully about what numbers are allowed. Do we want age in years, years and months, days, hours? Etc. For other types of measurements (e.g., gender), the values aren’t numerical. But, just as before, we need to think about what values are allowed. If we’re asking people to self-report their gender, what options to we allow them to choose between? Is it enough to allow only “male” or “female?” Do you need an “other” option? Or should we not give people any specific options, and let them answer in their own words? And if you open up the set of possible values to include all verbal response, how will you interpret their answers?

Operationalization is a tricky business, and there’s no “one, true way” to do it. The way in which you choose to operationalize the informal concept of “age” or “gender” into a formal measurement depends on what you need to use the measurement for. Often you’ll find that the community of scientists who work in your area have some fairly well-established ideas for how to go about it. In other words, operationalization needs to be thought through on a case by case basis. Nevertheless, while there a lot of issues that are specific to each individual research project, there are some aspects to it that are pretty general.

Before moving on, I want to take a moment to clear up our terminology, and in the process introduce one more term. Here are four different things that are closely related to each other:

A theoretical construct. This is the thing that you’re trying to take a measurement of, like “age,” “gender” or an “opinion.” A theoretical construct can’t be directly observed, and often they’re actually a bit vague.

A measure. The measure refers to the method or the tool that you use to make your observations. A question in a survey, a behavioural observation or a brain scan could all count as a measure.

An operationalization. The term “operationalization” refers to the logical connection between the measure and the theoretical construct, or to the process by which we try to derive a measure from a theoretical construct.

A variable. Finally, a new term. A variable is what we end up with when we apply our measure to something in the world. That is, variables are the actual “data” that we end up with in our data sets.

In practice, even scientists tend to blur the distinction between these things, but it’s very helpful to try to understand the differences.

1.8 Scales of measurement

As the previous section indicates, the outcome of a psychological measurement is called a variable. But not all variables are of the same qualitative type, and it’s very useful to understand what types there are. A very useful concept for distinguishing between different types of variables is what’s known as scales of measurement.

1.8.1 Nominal scale

A nominal scale variable (also referred to as a categorical variable) is one in which there is no particular relationship between the different possibilities: for these kinds of variables it doesn’t make any sense to say that one of them is ``bigger’ or “better” than any other one, and it absolutely doesn’t make any sense to average them. The classic example for this is “eye colour.” Eyes can be blue, green and brown, among other possibilities, but none of them is any “better” than any other one. As a result, it would feel really weird to talk about an “average eye colour.” Similarly, gender is nominal too: male isn’t better or worse than female, neither does it make sense to try to talk about an “average gender.” In short, nominal scale variables are those for which the only thing you can say about the different possibilities is that they are different. That’s it.

Let’s take a slightly closer look at this. Suppose I was doing research on how people commute to and from work. One variable I would have to measure would be what kind of transportation people use to get to work. This “transport type” variable could have quite a few possible values, including: “train,” “bus,” “car,” “bicycle,” etc. For now, let’s suppose that these four are the only possibilities, and suppose that when I ask 100 people how they got to work today, and I get this:

| Transportation | Number of people |

|---|---|

| (1) Train | 12 |

| (2) Bus | 30 |

| (3) Car | 48 |

| (4) Bicycle | 10 |

So, what’s the average transportation type? Obviously, the answer here is that there isn’t one. It’s a silly question to ask. You can say that travel by car is the most popular method, and travel by train is the least popular method, but that’s about all. Similarly, notice that the order in which I list the options isn’t very interesting. I could have chosen to display the data like this and nothing really changes.

| Transportation | Number of people |

|---|---|

| (3) Car | 48 |

| (1) Train | 12 |

| (4) Bicycle | 10 |

| (2) Bus | 30 |

1.8.2 Ordinal scale

Ordinal scale variables have a bit more structure than nominal scale variables, but not by a lot. An ordinal scale variable is one in which there is a natural, meaningful way to order the different possibilities, but you can’t do anything else. The usual example given of an ordinal variable is “finishing position in a race.” You can say that the person who finished first was faster than the person who finished second, but you don’t know how much faster. As a consequence we know that 1st \(>\) 2nd, and we know that 2nd \(>\) 3rd, but the difference between 1st and 2nd might be much larger than the difference between 2nd and 3rd.

Here’s an more psychologically interesting example. Suppose I’m interested in people’s attitudes to climate change, and I ask them to pick one of these four statements that most closely matches their beliefs:

- Temperatures are rising, because of human activity

- Temperatures are rising, but we don’t know why

- Temperatures are rising, but not because of humans

- Temperatures are not rising

Notice that these four statements actually do have a natural ordering, in terms of “the extent to which they agree with the current science.” Statement 1 is a close match, statement 2 is a reasonable match, statement 3 isn’t a very good match, and statement 4 is in strong opposition to the science. So, in terms of the thing I’m interested in (the extent to which people endorse the science), I can order the items as \(1 > 2 > 3 > 4\). Since this ordering exists, it would be very weird to list the options like this…

- Temperatures are rising, but not because of humans

- Temperatures are rising, because of human activity

- Temperatures are not rising

- Temperatures are rising, but we don’t know why

…because it seems to violate the natural “structure” to the question.

So, let’s suppose I asked 100 people these questions, and got the following answers:

| Number | |

|---|---|

| (1) Temperatures are rising, because of human activity | 51 |

| (2) Temperatures are rising, but we don’t know why | 20 |

| (3) Temperatures are rising, but not because of humans | 10 |

| (4) Temperatures are not rising | 19 |

When analysing these data, it seems quite reasonable to try to group (1), (2) and (3) together, and say that 81 of 100 people were willing to at least partially endorse the science. And it’s also quite reasonable to group (2), (3) and (4) together and say that 49 of 100 people registered at least some disagreement with the dominant scientific view. However, it would be entirely bizarre to try to group (1), (2) and (4) together and say that 90 of 100 people said…what? There’s nothing sensible that allows you to group those responses together at all.

That said, notice that while we can use the natural ordering of these items to construct sensible groupings, what we can’t do is average them. For instance, in my simple example here, the “average” response to the question is 1.97. If you can tell me what that means, I’d love to know. Because that sounds like gibberish to me!

1.8.3 Interval scale

In contrast to nominal and ordinal scale variables, interval scale and ratio scale variables are variables for which the numerical value is genuinely meaningful. In the case of interval scale variables, the differences between the numbers are interpretable, but the variable doesn’t have a “natural” zero value. A good example of an interval scale variable is measuring temperature in degrees celsius. For instance, if it was 15\(^\circ\) yesterday and 18\(^\circ\) today, then the 3\(^\circ\) difference between the two is genuinely meaningful. Moreover, that 3\(^\circ\) difference is exactly the same as the 3\(^\circ\) difference between \(7^\circ\) and \(10^\circ\). In short, addition and subtraction are meaningful for interval scale variables.

However, notice that the \(0^\circ\) does not mean “no temperature at all”: it actually means “the temperature at which water freezes,” which is pretty arbitrary. As a consequence, it becomes pointless to try to multiply and divide temperatures. It is wrong to say that \(20^\circ\) is twice as hot as \(10^\circ\), just as it is weird and meaningless to try to claim that \(20^\circ\) is negative two times as hot as \(-10^\circ\).

Again, lets look at a more psychological example. Suppose I’m interested in looking at how the attitudes of first-year university students have changed over time. Obviously, I’m going to want to record the year in which each student started. This is an interval scale variable. A student who started in 2003 did arrive 5 years before a student who started in 2008. However, it would be completely insane for me to divide 2008 by 2003 and say that the second student started “1.0024 times later” than the first one. That doesn’t make any sense at all.

1.8.4 Ratio scale

The fourth and final type of variable to consider is a ratio scale variable, in which zero really means zero, and it’s okay to multiply and divide. A good psychological example of a ratio scale variable is response time (RT). In a lot of tasks it’s very common to record the amount of time somebody takes to solve a problem or answer a question, because it’s an indicator of how difficult the task is. Suppose that Alan takes 2.3 seconds to respond to a question, whereas Ben takes 3.1 seconds. As with an interval scale variable, addition and subtraction are both meaningful here. Ben really did take \(3.1 - 2.3 = 0.8\) seconds longer than Alan did. However, notice that multiplication and division also make sense here too: Ben took \(3.1 / 2.3 = 1.35\) times as long as Alan did to answer the question. And the reason why you can do this is that, for a ratio scale variable such as RT, “zero seconds” really does mean “no time at all.”

1.8.5 Continuous versus discrete variables

There’s a second kind of distinction that you need to be aware of, regarding what types of variables you can run into. This is the distinction between continuous variables and discrete variables. The difference between these is as follows:

A continuous variable is one in which, for any two values that you can think of, it’s always logically possible to have another value in between.

A discrete variable is, in effect, a variable that isn’t continuous. For a discrete variable, it’s sometimes the case that there’s nothing in the middle.

These definitions probably seem a bit abstract, but they’re pretty simple once you see some examples. For instance, response time is continuous. If Alan takes 3.1 seconds and Ben takes 2.3 seconds to respond to a question, then it’s possible for Cameron’s response time to lie in between, by taking 3.0 seconds. And of course it would also be possible for David to take 3.031 seconds to respond, meaning that his RT would lie in between Cameron’s and Alan’s. And while in practice it might be impossible to measure RT that precisely, it’s certainly possible in principle. Because we can always find a new value for RT in between any two other ones, we say that RT is continuous.

Discrete variables occur when this rule is violated. For example, nominal scale variables are always discrete: there isn’t a type of transportation that falls “in between” trains and bicycles, not in the strict mathematical way that 2.3 falls in between 2 and 3. So transportation type is discrete. Similarly, ordinal scale variables are always discrete: although “2nd place” does fall between “1st place” and “3rd place,” there’s nothing that can logically fall in between “1st place” and “2nd place.” Interval scale and ratio scale variables can go either way. As we saw above, response time (a ratio scale variable) is continuous. Temperature in degrees celsius (an interval scale variable) is also continuous. However, the year you went to school (an interval scale variable) is discrete. There’s no year in between 2002 and 2003. The number of questions you get right on a true-or-false test (a ratio scale variable) is also discrete: since a true-or-false question doesn’t allow you to be “partially correct,” there’s nothing in between 5/10 and 6/10. The table summarizes the relationship between the scales of measurement and the discrete/continuity distinction. Cells with a tick mark correspond to things that are possible. I’m trying to hammer this point home, because (a) some textbooks get this wrong, and (b) people very often say things like “discrete variable” when they mean “nominal scale variable.” It’s very unfortunate.

| continuous | discrete | |

|---|---|---|

| nominal | x | |

| ordinal | x | |

| interval | x | x |

| ratio | x | x |

1.8.6 Some complexities

Okay, I know you’re going to be shocked to hear this, but …the real world is much messier than this little classification scheme suggests. Very few variables in real life actually fall into these nice neat categories, so you need to be kind of careful not to treat the scales of measurement as if they were hard and fast rules. It doesn’t work like that: they’re guidelines, intended to help you think about the situations in which you should treat different variables differently. Nothing more.

So let’s take a classic example, maybe the classic example, of a psychological measurement tool: the Likert scale. The humble Likert scale is the bread and butter tool of all survey design. You yourself have filled out hundreds, maybe thousands of them, and odds are you’ve even used one yourself. Suppose we have a survey question that looks like this:

Which of the following best describes your opinion of the statement that “all pirates are freaking awesome” …

and then the options presented to the participant are these:

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Neither agree nor disagree

(4) Agree

(5) Strongly agree

This set of items is an example of a 5-point Likert scale: people are asked to choose among one of several (in this case 5) clearly ordered possibilities, generally with a verbal descriptor given in each case. However, it’s not necessary that all items be explicitly described. This is a perfectly good example of a 5-point Likert scale too:

(1) Strongly disagree

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5) Strongly agree

Likert scales are very handy, if somewhat limited, tools. The question is, what kind of variable are they? They’re obviously discrete, since you can’t give a response of 2.5. They’re obviously not nominal scale, since the items are ordered; and they’re not ratio scale either, since there’s no natural zero.

But are they ordinal scale or interval scale? One argument says that we can’t really prove that the difference between “strongly agree” and “agree” is of the same size as the difference between “agree” and “neither agree nor disagree.” In fact, in everyday life it’s pretty obvious that they’re not the same at all. So this suggests that we ought to treat Likert scales as ordinal variables. On the other hand, in practice most participants do seem to take the whole “on a scale from 1 to 5” part fairly seriously, and they tend to act as if the differences between the five response options were fairly similar to one another. As a consequence, a lot of researchers treat Likert scale data as if it were interval scale. It’s not interval scale, but in practice it’s close enough that we usually think of it as being quasi-interval scale.

1.9 Assessing the reliability of a measurement

At this point we’ve thought a little bit about how to operationalize a theoretical construct and thereby create a psychological measure; and we’ve seen that by applying psychological measures we end up with variables, which can come in many different types. At this point, we should start discussing the obvious question: is the measurement any good? We’ll do this in terms of two related ideas: reliability and validity. Put simply, the reliability of a measure tells you how precisely you are measuring something, whereas the validity of a measure tells you how accurate the measure is.

Reliability is actually a very simple concept: it refers to the repeatability or consistency of your measurement. The measurement of my weight by means of a “bathroom scale” is very reliable: if I step on and off the scales over and over again, it’ll keep giving me the same answer. Measuring my intelligence by means of “asking my mom” is very unreliable: some days she tells me I’m a bit thick, and other days she tells me I’m a complete moron. Notice that this concept of reliability is different to the question of whether the measurements are correct (the correctness of a measurement relates to it’s validity). If I’m holding a sack of potatos when I step on and off of the bathroom scales, the measurement will still be reliable: it will always give me the same answer. However, this highly reliable answer doesn’t match up to my true weight at all, therefore it’s wrong. In technical terms, this is a reliable but invalid measurement. Similarly, while my mom’s estimate of my intelligence is a bit unreliable, she might be right. Maybe I’m just not too bright, and so while her estimate of my intelligence fluctuates pretty wildly from day to day, it’s basically right. So that would be an unreliable but valid measure. Of course, to some extent, notice that if my mum’s estimates are too unreliable, it’s going to be very hard to figure out which one of her many claims about my intelligence is actually the right one. To some extent, then, a very unreliable measure tends to end up being invalid for practical purposes; so much so that many people would say that reliability is necessary (but not sufficient) to ensure validity.

Okay, now that we’re clear on the distinction between reliability and validity, let’s have a think about the different ways in which we might measure reliability:

Test-retest reliability. This relates to consistency over time: if we repeat the measurement at a later date, do we get a the same answer?

Inter-rater reliability. This relates to consistency across people: if someone else repeats the measurement (e.g., someone else rates my intelligence) will they produce the same answer?

Parallel forms reliability. This relates to consistency across theoretically-equivalent measurements: if I use a different set of bathroom scales to measure my weight, does it give the same answer?

Internal consistency reliability. If a measurement is constructed from lots of different parts that perform similar functions (e.g., a personality questionnaire result is added up across several questions) do the individual parts tend to give similar answers.

Not all measurements need to possess all forms of reliability. For instance, educational assessment can be thought of as a form of measurement. One of the subjects that I teach, Computational Cognitive Science, has an assessment structure that has a research component and an exam component (plus other things). The exam component is intended to measure something different from the research component, so the assessment as a whole has low internal consistency. However, within the exam there are several questions that are intended to (approximately) measure the same things, and those tend to produce similar outcomes; so the exam on its own has a fairly high internal consistency. Which is as it should be. You should only demand reliability in those situations where you want to be measure the same thing!

1.10 The role of variables: predictors and outcomes

Okay, I’ve got one last piece of terminology that I need to explain to you before moving away from variables. Normally, when we do some research we end up with lots of different variables. Then, when we analyse our data we usually try to explain some of the variables in terms of some of the other variables. It’s important to keep the two roles “thing doing the explaining” and “thing being explained” distinct. So let’s be clear about this now. Firstly, we might as well get used to the idea of using mathematical symbols to describe variables, since it’s going to happen over and over again. Let’s denote the “to be explained” variable \(Y\), and denote the variables “doing the explaining” as \(X_1\), \(X_2\), etc.

Now, when we doing an analysis, we have different names for \(X\) and \(Y\), since they play different roles in the analysis. The classical names for these roles are independent variable (IV) and dependent variable (DV). The IV is the variable that you use to do the explaining (i.e., \(X\)) and the DV is the variable being explained (i.e., \(Y\)). The logic behind these names goes like this: if there really is a relationship between \(X\) and \(Y\) then we can say that \(Y\) depends on \(X\), and if we have designed our study “properly” then \(X\) isn’t dependent on anything else. However, I personally find those names horrible: they’re hard to remember and they’re highly misleading, because (a) the IV is never actually “independent of everything else” and (b) if there’s no relationship, then the DV doesn’t actually depend on the IV. And in fact, because I’m not the only person who thinks that IV and DV are just awful names, there are a number of alternatives that I find more appealing.

For example, in an experiment the IV refers to the manipulation, and the DV refers to the measurement. So, we could use manipulated variable (independent variable) and measured variable (dependent variable).

| role of the variable | classical name | modern name |

|---|---|---|

| “to be explained” | dependent variable (DV) | Measurement |

| “to do the explaining” | independent variable (IV) | Manipulation |

We could also use predictors and outcomes. The idea here is that what you’re trying to do is use \(X\) (the predictors) to make guesses about \(Y\) (the outcomes). This is summarized in the table:

| role of the variable | classical name | modern name |

|---|---|---|

| “to be explained” | dependent variable (DV) | outcome |

| “to do the explaining” | independent variable (IV) | predictor |

1.11 Experimental and non-experimental research

One of the big distinctions that you should be aware of is the distinction between “experimental research” and “non-experimental research.” When we make this distinction, what we’re really talking about is the degree of control that the researcher exercises over the people and events in the study.

1.11.1 Experimental research

The key features of experimental research is that the researcher controls all aspects of the study, especially what participants experience during the study. In particular, the researcher manipulates or varies something (IVs), and then allows the outcome variable (DV) to vary naturally. The idea here is to deliberately vary the something in the world (IVs) to see if it has any causal effects on the outcomes. Moreover, in order to ensure that there’s no chance that something other than the manipulated variable is causing the outcomes, everything else is kept constant or is in some other way “balanced” to ensure that they have no effect on the results. In practice, it’s almost impossible to think of everything else that might have an influence on the outcome of an experiment, much less keep it constant. The standard solution to this is randomization: that is, we randomly assign people to different groups, and then give each group a different treatment (i.e., assign them different values of the predictor variables). We’ll talk more about randomization later in this course, but for now, it’s enough to say that what randomization does is minimize (but not eliminate) the chances that there are any systematic difference between groups.

Let’s consider a very simple, completely unrealistic and grossly unethical example. Suppose you wanted to find out if smoking causes lung cancer. One way to do this would be to find people who smoke and people who don’t smoke, and look to see if smokers have a higher rate of lung cancer. This is not a proper experiment, since the researcher doesn’t have a lot of control over who is and isn’t a smoker. And this really matters: for instance, it might be that people who choose to smoke cigarettes also tend to have poor diets, or maybe they tend to work in asbestos mines, or whatever. The point here is that the groups (smokers and non-smokers) actually differ on lots of things, not just smoking. So it might be that the higher incidence of lung cancer among smokers is caused by something else, not by smoking per se. In technical terms, these other things (e.g. diet) are called “confounds,” and we’ll talk about those in just a moment.

In the meantime, let’s now consider what a proper experiment might look like. Recall that our concern was that smokers and non-smokers might differ in lots of ways. The solution, as long as you have no ethics, is to control who smokes and who doesn’t. Specifically, if we randomly divide participants into two groups, and force half of them to become smokers, then it’s very unlikely that the groups will differ in any respect other than the fact that half of them smoke. That way, if our smoking group gets cancer at a higher rate than the non-smoking group, then we can feel pretty confident that (a) smoking does cause cancer and (b) we’re murderers.

1.11.2 Non-experimental research

Non-experimental research is a broad term that covers “any study in which the researcher doesn’t have quite as much control as they do in an experiment.” Obviously, control is something that scientists like to have, but as the previous example illustrates, there are lots of situations in which you can’t or shouldn’t try to obtain that control. Since it’s grossly unethical (and almost certainly criminal) to force people to smoke in order to find out if they get cancer, this is a good example of a situation in which you really shouldn’t try to obtain experimental control. But there are other reasons too. Even leaving aside the ethical issues, our “smoking experiment” does have a few other issues. For instance, when I suggested that we “force” half of the people to become smokers, I must have been talking about starting with a sample of non-smokers, and then forcing them to become smokers. While this sounds like the kind of solid, evil experimental design that a mad scientist would love, it might not be a very sound way of investigating the effect in the real world. For instance, suppose that smoking only causes lung cancer when people have poor diets, and suppose also that people who normally smoke do tend to have poor diets. However, since the “smokers” in our experiment aren’t “natural” smokers (i.e., we forced non-smokers to become smokers; they didn’t take on all of the other normal, real life characteristics that smokers might tend to possess) they probably have better diets. As such, in this silly example they wouldn’t get lung cancer, and our experiment will fail, because it violates the structure of the “natural” world (the technical name for this is an “artifactual” result; see later).

One distinction worth making between two types of non-experimental research is the difference between quasi-experimental research and case studies. The example I discussed earlier – in which we wanted to examine incidence of lung cancer among smokers and non-smokers, without trying to control who smokes and who doesn’t – is a quasi-experimental design. That is, it’s the same as an experiment, but we don’t control the predictors (IVs). We can still use statistics to analyse the results, it’s just that we have to be a lot more careful.

The alternative approach, case studies, aims to provide a very detailed description of one or a few instances. In general, you can’t use statistics to analyse the results of case studies, and it’s usually very hard to draw any general conclusions about “people in general” from a few isolated examples. However, case studies are very useful in some situations. Firstly, there are situations where you don’t have any alternative: neuropsychology has this issue a lot. Sometimes, you just can’t find a lot of people with brain damage in a specific area, so the only thing you can do is describe those cases that you do have in as much detail and with as much care as you can. However, there’s also some genuine advantages to case studies: because you don’t have as many people to study, you have the ability to invest lots of time and effort trying to understand the specific factors at play in each case. This is a very valuable thing to do. As a consequence, case studies can complement the more statistically-oriented approaches that you see in experimental and quasi-experimental designs. We won’t talk much about case studies in these lectures, but they are nevertheless very valuable tools!

1.12 Assessing the validity of a study

More than any other thing, a scientist wants their research to be “valid.” The conceptual idea behind validity is very simple: can you trust the results of your study? If not, the study is invalid. However, while it’s easy to state, in practice it’s much harder to check validity than it is to check reliability. And in all honesty, there’s no precise, clearly agreed upon notion of what validity actually is. In fact, there’s lots of different kinds of validity, each of which raises it’s own issues, and not all forms of validity are relevant to all studies. I’m going to talk about five different types:

Internal validity

External validity

Construct validity

Face validity

Ecological validity

To give you a quick guide as to what matters here…(1) Internal and external validity are the most important, since they tie directly to the fundamental question of whether your study really works. (2) Construct validity asks whether you’re measuring what you think you are. (3) Face validity isn’t terribly important except insofar as you care about “appearances.” (4) Ecological validity is a special case of face validity that corresponds to a kind of appearance that you might care about a lot.

1.12.1 Internal validity

Internal validity refers to the extent to which you are able draw the correct conclusions about the causal relationships between variables. It’s called “internal” because it refers to the relationships between things “inside” the study. Let’s illustrate the concept with a simple example. Suppose you’re interested in finding out whether a university education makes you write better. To do so, you get a group of first year students, ask them to write a 1000 word essay, and count the number of spelling and grammatical errors they make. Then you find some third-year students, who obviously have had more of a university education than the first-years, and repeat the exercise. And let’s suppose it turns out that the third-year students produce fewer errors. And so you conclude that a university education improves writing skills. Right? Except… the big problem that you have with this experiment is that the third-year students are older, and they’ve had more experience with writing things. So it’s hard to know for sure what the causal relationship is: Do older people write better? Or people who have had more writing experience? Or people who have had more education? Which of the above is the true cause of the superior performance of the third-years? Age? Experience? Education? You can’t tell. This is an example of a failure of internal validity, because your study doesn’t properly tease apart the causal relationships between the different variables.

1.12.2 External validity

External validity relates to the generalizability of your findings. That is, to what extent do you expect to see the same pattern of results in “real life” as you saw in your study. To put it a bit more precisely, any study that you do in psychology will involve a fairly specific set of questions or tasks, will occur in a specific environment, and will involve participants that are drawn from a particular subgroup. So, if it turns out that the results don’t actually generalize to people and situations beyond the ones that you studied, then what you’ve got is a lack of external validity.

The classic example of this issue is the fact that a very large proportion of studies in psychology will use undergraduate psychology students as the participants. Obviously, however, the researchers don’t care only about psychology students; they care about people in general. Given that, a study that uses only psych students as participants always carries a risk of lacking external validity. That is, if there’s something “special” about psychology students that makes them different to the general populace in some relevant respect, then we may start worrying about a lack of external validity.

That said, it is absolutely critical to realize that a study that uses only psychology students does not necessarily have a problem with external validity. I’ll talk about this again later, but it’s such a common mistake that I’m going to mention it here. The external validity is threatened by the choice of population if (a) the population from which you sample your participants is very narrow (e.g., psych students), and (b) the narrow population that you sampled from is systematically different from the general population, in some respect that is relevant to the psychological phenomenon that you intend to study. The italicized part is the bit that lots of people forget: it is true that psychology undergraduates differ from the general population in lots of ways, and so a study that uses only psych students may have problems with external validity. However, if those differences aren’t very relevant to the phenomenon that you’re studying, then there’s nothing to worry about. To make this a bit more concrete, here’s two extreme examples:

You want to measure “attitudes of the general public towards psychotherapy,” but all of your participants are psychology students. This study would almost certainly have a problem with external validity.

You want to measure the effectiveness of a visual illusion, and your participants are all psychology students. This study is very unlikely to have a problem with external validity

Having just spent the last couple of paragraphs focusing on the choice of participants (since that’s the big issue that everyone tends to worry most about), it’s worth remembering that external validity is a broader concept. The following are also examples of things that might pose a threat to external validity, depending on what kind of study you’re doing:

People might answer a “psychology questionnaire” in a manner that doesn’t reflect what they would do in real life.

Your lab experiment on (say) “human learning” has a different structure to the learning problems people face in real life.

1.12.3 Construct validity

Construct validity is basically a question of whether you’re measuring what you want to be measuring. A measurement has good construct validity if it is actually measuring the correct theoretical construct, and bad construct validity if it doesn’t. To give very simple (if ridiculous) example, suppose I’m trying to investigate the rates with which university students cheat on their exams. And the way I attempt to measure it is by asking the cheating students to stand up in the lecture theatre so that I can count them. When I do this with a class of 300 students, 0 people claim to be cheaters. So I therefore conclude that the proportion of cheaters in my class is 0%. Clearly this is a bit ridiculous. But the point here is not that this is a very deep methodological example, but rather to explain what construct validity is. The problem with my measure is that while I’m trying to measure “the proportion of people who cheat” what I’m actually measuring is “the proportion of people stupid enough to own up to cheating, or bloody minded enough to pretend that they do.” Obviously, these aren’t the same thing! So my study has gone wrong, because my measurement has very poor construct validity.

1.12.4 Face validity

Face validity simply refers to whether or not a measure “looks like” it’s doing what it’s supposed to, nothing more. If I design a test of intelligence, and people look at it and they say “no, that test doesn’t measure intelligence,” then the measure lacks face validity. It’s as simple as that. Obviously, face validity isn’t very important from a pure scientific perspective. After all, what we care about is whether or not the measure actually does what it’s supposed to do, not whether it looks like it does what it’s supposed to do. As a consequence, we generally don’t care very much about face validity. That said, the concept of face validity serves three useful pragmatic purposes:

Sometimes, an experienced scientist will have a “hunch” that a particular measure won’t work. While these sorts of hunches have no strict evidentiary value, it’s often worth paying attention to them. Because often times people have knowledge that they can’t quite verbalize, so there might be something to worry about even if you can’t quite say why. In other words, when someone you trust criticizes the face validity of your study, it’s worth taking the time to think more carefully about your design to see if you can think of reasons why it might go awry. Mind you, if you don’t find any reason for concern, then you should probably not worry: after all, face validity really doesn’t matter much.

Often (very often), completely uninformed people will also have a “hunch” that your research is crap. And they’ll criticize it on the internet or something. On close inspection, you’ll often notice that these criticisms are actually focused entirely on how the study “looks,” but not on anything deeper. The concept of face validity is useful for gently explaining to people that they need to substantiate their arguments further.

Expanding on the last point, if the beliefs of untrained people are critical (e.g., this is often the case for applied research where you actually want to convince policy makers of something or other) then you have to care about face validity. Simply because – whether you like it or not – a lot of people will use face validity as a proxy for real validity. If you want the government to change a law on scientific, psychological grounds, then it won’t matter how good your studies “really” are. If they lack face validity, you’ll find that politicians ignore you. Of course, it’s somewhat unfair that policy often depends more on appearance than fact, but that’s how things go.

1.12.5 Ecological validity

Ecological validity is a different notion of validity, which is similar to external validity, but less important. The idea is that, in order to be ecologically valid, the entire set up of the study should closely approximate the real world scenario that is being investigated. In a sense, ecological validity is a kind of face validity – it relates mostly to whether the study “looks” right, but with a bit more rigour to it. To be ecologically valid, the study has to look right in a fairly specific way. The idea behind it is the intuition that a study that is ecologically valid is more likely to be externally valid. It’s no guarantee, of course. But the nice thing about ecological validity is that it’s much easier to check whether a study is ecologically valid than it is to check whether a study is externally valid. An simple example would be eyewitness identification studies. Most of these studies tend to be done in a university setting, often with fairly simple array of faces to look at rather than a line up. The length of time between seeing the “criminal” and being asked to identify the suspect in the “line up” is usually shorter. The “crime” isn’t real, so there’s no chance that the witness being scared, and there’s no police officers present, so there’s not as much chance of feeling pressured. These things all mean that the study definitely lacks ecological validity. They might (but might not) mean that it also lacks external validity.

1.13 Confounds, artifacts and other threats to validity

If we look at the issue of validity in the most general fashion, the two biggest worries that we have are confounds and artifact. These two terms are defined in the following way:

Confound: A confound is an additional, often unmeasured variable that turns out to be related to both the predictors and the outcomes. The existence of confounds threatens the internal validity of the study because you can’t tell whether the predictor causes the outcome, or if the confounding variable causes it, etc.

Artifact: A result is said to be “artifactual” if it only holds in the special situation that you happened to test in your study. The possibility that your result is an artifact describes a threat to your external validity, because it raises the possibility that you can’t generalize your results to the actual population that you care about.

As a general rule confounds are a bigger concern for non-experimental studies, precisely because they’re not proper experiments: by definition, you’re leaving lots of things uncontrolled, so there’s a lot of scope for confounds working their way into your study. Experimental research tends to be much less vulnerable to confounds: the more control you have over what happens during the study, the more you can prevent confounds from appearing.

However, there’s always swings and roundabouts, and when we start thinking about artifacts rather than confounds, the shoe is very firmly on the other foot. For the most part, artifactual results tend to be a concern for experimental studies than for non-experimental studies. To see this, it helps to realize that the reason that a lot of studies are non-experimental is precisely because what the researcher is trying to do is examine human behaviour in a more naturalistic context. By working in a more real-world context, you lose experimental control (making yourself vulnerable to confounds) but because you tend to be studying human psychology “in the wild” you reduce the chances of getting an artifactual result. Or, to put it another way, when you take psychology out of the wild and bring it into the lab (which we usually have to do to gain our experimental control), you always run the risk of accidentally studying something different than you wanted to study: which is more or less the definition of an artifact.

Be warned though: the above is a rough guide only. It’s absolutely possible to have confounds in an experiment, and to get artifactual results with non-experimental studies. This can happen for all sorts of reasons, not least of which is researcher error. In practice, it’s really hard to think everything through ahead of time, and even very good researchers make mistakes. But other times it’s unavoidable, simply because the researcher has ethics (e.g., see “differential attrition”).

Okay. There’s a sense in which almost any threat to validity can be characterized as a confound or an artifact: they’re pretty vague concepts. So let’s have a look at some of the most common examples…

1.13.1 History effects

History effects refer to the possibility that specific events may occur during the study itself that might influence the outcomes. For instance, something might happen in between a pre-test and a post-test. Or, in between testing participant 23 and participant 24. Alternatively, it might be that you’re looking at an older study, which was perfectly valid for its time, but the world has changed enough since then that the conclusions are no longer trustworthy. Examples of things that would count as history effects:

You’re interested in how people think about risk and uncertainty. You started your data collection in December 2010. But finding participants and collecting data takes time, so you’re still finding new people in February 2011. Unfortunately for you (and even more unfortunately for others), the Queensland floods occurred in January 2011, causing billions of dollars of damage and killing many people. Not surprisingly, the people tested in February 2011 express quite different beliefs about handling risk than the people tested in December 2010. Which (if any) of these reflects the “true” beliefs of participants? I think the answer is probably both: the Queensland floods genuinely changed the beliefs of the Australian public, though possibly only temporarily. The key thing here is that the “history” of the people tested in February is quite different to people tested in December.

You’re testing the psychological effects of a new anti-anxiety drug. So what you do is measure anxiety before administering the drug (e.g., by self-report, and taking physiological measures, let’s say), then you administer the drug, and then you take the same measures afterwards. In the middle, however, because your labs are in Los Angeles, there’s an earthquake, which increases the anxiety of the participants.

1.13.2 Maturation effects

As with history effects, maturational effects are fundamentally about change over time. However, maturation effects aren’t in response to specific events. Rather, they relate to how people change on their own over time: we get older, we get tired, we get bored, etc. Some examples of maturation effects:

When doing developmental psychology research, you need to be aware that children grow up quite rapidly. So, suppose that you want to find out whether some educational trick helps with vocabulary size among 3 year olds. One thing that you need to be aware of is that the vocabulary size of children that age is growing at an incredible rate (multiple words per day), all on its own. If you design your study without taking this maturational effect into account, then you won’t be able to tell if your educational trick works.

When running a very long experiment in the lab (say, something that goes for 3 hours), it’s very likely that people will begin to get bored and tired, and that this maturational effect will cause performance to decline, regardless of anything else going on in the experiment

1.13.3 Repeated testing effects